What’s a whoop-to-do lever?

This month you will find out why Mr. Kirby calls torque amplifiers whoop te-do-levers. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who has ever had a friendly rivalry with a Farmall fan. In fact, many have speculated that International Harvester’s refusal to change to a better type transmission was one of the leading factors in its eventual demise.

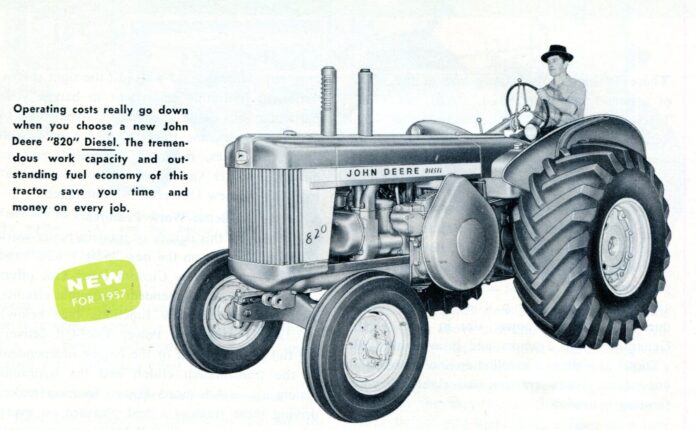

We come to another important modification or change in our tractor. It is actually the changes in both the 820 and 720 diesel tractors. When I talk about these diesel improvements, gentlemen, you find them in both models. I am going to talk basically about the 820 here to start with, but what I say about it will be true of the 720 with the exception of the injection pump.

When we came out with the 820, it had 67.64 belt horsepower. Last fall, we boosted this to 75.06 horsepower. How have we done it? The engine has the same bore and stroke and speed. You can increase horsepower in an engine one of several ways. You can increase the bore or the stroke or both and increase the size or cubic inch displacement of the engine. You can increase the speed of the engine or you can increase the amount of material that you burn in the engine. That’s what we have done. We are burning more now in the same size of engine—that is how we got the gain in horsepower. Now, why are we doing that? Well, we do that, mind you, because of course you know your compression pressures go up, and consequently, the wear and tear in your engine goes up. But we can do that now where we couldn’t in the past because we spent a lot of money in learning how to do a job and we are still spending money in doing the job, about $9 a piece on each one of these piston ring combinations. We are doing this with a device called the Keystone piston ring. It is called Keystone because in its shape, it is similar to the keystone in a masonry arch. It’s a bead shaped proposition, flat on the bottom and flat on the top and that works in a groove in the top of the piston that is machined with the same contour shape to it.

Now you see a normal piston ring operation, fellows, is the pistons going up and down the cylinder. The edge of that ring as the piston comes up is pitch down because this edge of the piston ring is leading into the cylinder wall scraping and the ring all around is distorted in that manner. Then when the piston gets up on top and starts down, the ring works the other way. Now if there is any particle of carbon or by-product of combustion that gets back or any of the tars or gums found in today’s diesel fuel that get in this area and harden, they are worked back down into the ring groove and generally become so plentiful in there that you clog the piston ring groove and the ring in the groove so that no longer does the ring expand or contract. Then it is a short period of time before the surface of the ring is worn or the cylinder is worn and you have excessive clearance; then you go down and the next ring is the same way until finally you need to re-ring your engine. If that doesn’t hold true, if you try to put enough ring pressure on here, you beat out the soft aluminum ring land in the aluminum piston.

In your May 10 issue of Farm Implement News, they had quite an article in it about this cleaning out of top ring surfaces, particularly with chrome rings in engines today and that wasn’t talking about our engines. We didn’t have that trouble with this piston to any great degree because we kept down the overall performance of the engine. We didn’t build such a big fire in the cylinder. We didn’t have such extraordinary stresses, but we get by with it today, fellows, because in that top ring area of the model 820 and 720 pistons, we’ve got a cast steel ring cast in the top area there to give us a hard surface for this Keystone ring to work in. Now as that Keystone ring wobbles back and forth in the ring groove, we take advantage of this wobble; it’s the same as a pair of scissors trying to clamp down on a round piece of steel bar. What happens if you took a pair of scissors and tried to cut that bar—it would roll right out. It’s the same principle that causes this to be a self cleaning type of ring so that we don’t have that built up in there in the first place. Consequently, much better ring life and we could go up in performance on the 820 engine by building this bigger fire in it. Remember that is true in the 720 as well as the 820.

The crankshaft, the camshaft and the crankshaft of the starting engine have been increased in main bearing size to offer more stability in that starting engine. We have done a lot of work in this area on our diesel engine. The camshaft lift has been smoothed out so that we don’t give quite as much shock to our valve training. If there was any point of weakness in the starting engine, fellows, I think it would be in the valve train of the starting engine. We have done a lot of work there. We have increased drastically the size of the push rod, given it much more strength. It has a forged end on both ends of it for good wearing surfaces. We have changed the design of the rocker arms themselves. We were having a little trouble maintaining tappet clearance in the starting engine and it was found out to be caused from the fact that to get proper tappet clearance, we sometimes had to screw the screw down so far in the rocker arm that we didn’t get much of a purchase with a little locking nut on top. We have corrected that now by milling off this head of the rocker arm so tha t we do get more threads in contact with the nut here to ensure that the thing remains locked like it should and that we maintain our proper tappet clearance.

We have an automatic fuel shutoff now on the line of diesel tractors and it is much the same device that we have on the gasoline tractor and it does a pretty good job for us, preventing any possible leakage of fuel between the gas tank and the rest of the engine. Now along with this automatic fuel shutoff in both the 820 and the 720, we’ve got another device, a little make and break pressure switch that is hooked up in the circuit of the little warning light on the dash—the purpose of which is to make that dash light indicate not only the ignition switch being on but also to give you an indication that you’ve got oil pressure in the starting engine. When that switch is used and you turn on your ignition switch, the light will come on.

As soon as you start your starting engine, three to five pounds of oil pressure will break this contact so that your little pilot light on the dash goes out; then should you have oil failure in the starting engine while it is still running as that light comes back on, you will notice it, but the light will not come on if your oil pressure is maintained until you either shut off the switch or shut the starting engine off like you should be turning off the fuel supply and burning the fuel out. Then if you shut your starting engine off like that, your light will come back on because your oil pressure has dropped now; it will come back on, indicating to you to reach down and turn off your ignition switch so you don’t cause an unnecessary drain on your tractor battery. It is a very welcome little device for diesel engines.

In general, we have improved on the row crop tractor in the entire line by what you know now as a black faced dash, the new steering wheel, the step, the sealed beam headlights—these are very obvious changes not of any real great magnitude, but certainly of some. A nice thing that you probably will never recognize and incidentally, how do you like this black muffler? Is it standing up for you? Inside of this muffler today, we have a stainless steel tube forming the inner wall, of course, promoting much greater muffler life. Remember I told you about water vapor, the byproduct of combustion; it’s the same water vapor that rusts out the muffler on your cars.

Power adjusted rear wheels now being offered on the Waterloo line of tractors differ from what your competitors have in the fact that you do not have to change wheels from side to side to go from maximum to minimum tread setting. You know, we retained that thought when we put the adjustment on the axle and when you have power adjusted wheels, you get some of the adjustment with the power adjusted wheels, some of it with a rack and pinion on the axle. Power adjusted rear wheels on the 520 and 620 give you from 56 to 94-inch tread adjustment, 60 to 94 in the 720. This is about the widest tread range on any normal row crop tractor.

This idea of not having to reverse the wheels must be of some importance, fellows, because I’ll point out a little incident to you. This International 450 tractor came over here directly from the branch organization, as I understand it, and that is the way the tractor was shipped from the factory. You will notice the rear wheels on that job are put into the narrow position for shipping, much the same as we do from Waterloo. You look at those rear wheels a little closer and you will see that the tread is backward on there. Am I right or wrong? Now, why is it backwards? We thought about it here for a minute and I’ll give you the answer. That is so that the dealer can jack up one side of that tractor, take a wheel off, tum it around and the tread will be on forward and then his wheel will be in the normal attitude that it is generally used. It is not necessary for the dealer to jack up both sides of the tractor at once, taking both wheels clear off and then reversing them. Now the International Harvester Corp. thinks that it is important enough to make this little safety precaution for their dealers, let alone for their farmers. It certainly must mean something out in the field as far as our not having to do it all.

You fellows have probably all been informed about the 8-1/3 mile per hour forward gear being offered in the 720 transmission now—one that a lot of people have requested as a rotary hoe or harrowing speed. You know how to order that from the factory, but we do have one other gear option on the 720 line and that is in fourth gear, changing it from 4-1/3 to 4-3/4 mile per hour. Now when you do so, it will allow a 720 tractor to compete much more successfully against the older 70 and some of the older John Deere tractors in that particular gear. Not only that, but it would change the sixth speed of 11-1/4 up to 12-1/ 2. This may be desired by some of you. It is available as factory equipment and it also is going to be available in the field, but I don’t think it will be of much impor tance in your branch.

Let’s talk about some of our competitor’s transmissions for a minute. You know there are a lot of remarks being made today about 8, 10 and 12 speed transmissions, a lot of hulla-balloo over it. International has got its torque amplifier; these people have got power director and somebody else has got ampli-torque. They are all designed to do one thing and that’s to greatly enhance the tractor’s value in the field by offering such a wide variety of ground travel—that’s what they tell you.

Now, I’ll make one concession—under certain operating conditions and harvesting conditions, I like this torque amplification idea really well. It’s got some value under certain harvesting conditions. If you have rolling ground where the amount of crop range varies greatly enough or you have an alternately wet and dry field where you are going to have a tremendous difference in the heaviness of your crop, then they are a wonderful thing for harvesting.

Now, of course, in actual practice, not a great deal of time (compared to the total time the tractor is used in a year) is used in harvesting and, of course, the amount of time that you have this much variance in field conditions is rather small so I am a little inclined to believe that the real functional purpose of the ampli-torque type system or a power director or a torque amplifier isn’t as important as we would be led to believe. I’ll tell you what they will do on the drawbar for you. They’re a darn good torque substitute. Remember I told you about making this torque test out at the University of Nebraska and the fallacy of it. Whether you’ve got a torque amplifier or not to play with, if you load your tractor in the field like I indicated for you to do, you can ask the man with all the kind of sticks on it for controls that he can get to come in and duplicate what you’ve got and he can’t do it. Because what happens each time he pulls one of these sticks, he just keeps further and further behind you. He just completely cuts down his ground travel speed to the point where he is not getting anywhere.

Look at Minneapolis Moline Five Star and I’ll quote you their road speed here so you can easier see the ratio: 16.21 mph in straight drive and he pulls his ampli-torque lever and he cuts his speed down to 8.51, just in half. Well now, my reasoning is this, fellows, if your tractor hasn’t got enough torque in it so that you can plow normally in a given gear and you have to increase your torque by twice to get through the place, there is something wrong with it. Your field conditions, while they vary greatly, don’t vary in a two to one ratio, I mean should you be using a four bottom plow or a two bottom. There isn’t a lever in the world that is going to make that much difference on your tractor operation.

Look at International in its 450: 16.7 to 11.3—now that’s not quite two to one, but it’s almost as bad. I think we all recognize that people are criticizing the fact that when you put International in third straight drive and pull the torque amplifier back and go down under, you go below what you do in normal second gear. It doesn’t make sense. It is that thing that will cause them to stay further behind you in operating for a given length of time. They just lose out if they’ve got to pull that lever to keep going and you load your tractors like I’ve asked you to and they’ll have to pull that lever or they’ll kill out.

The same is true in the Allis Chalmers with its power director. Now the Allis-Chalmers power director, I didn’t understand how it worked too well; it’s the same type of system that you have in the International tractor with exception of the hand clutch as a multiple disk wet type clutch and it is possible to slip that clutch for short periods of time. In other words, if you have it in high and you want to just momentarily slow your tractor down a little bit, you can slip that wet type clutch. The wet type clutch can be likened very much to the safety clutch that we have in our power shaft; you know, we have a separate little oil pump on there and we pump oil through the plates of our power shaft so when we do slip it, that heat of friction is dissipated and doesn’t bum out our clutch.

Incidentally, that’s a pretty dam good safety arrangement on a power shaft compared to what your competitor has. That tractor there you know has got a pin through a device, a shear pin. Well, you don’t shear that many more times before you’ve got the whole assembly to a point where it just won’t work. That’s the kind of protection they have in that tractor. Oliver on the power shaft—they cut down a section of the shaft and just end up twisting off one shaft each time. I imagine that’s pretty good repair business, but don’t be alarmed about these whoop-te-do levers. All that glitters is not gold.

Let me tell you something now about this new line of Case tractors that is coming out. This is great stuff they are flying down to New Mexico to see. The Case tractors have got quite a variety of transmissions in them. They’ve got what they call, first of all, they’ve got in most all their tractors a regular four speed transmission. Then you can expand the function of the tractor and make a whole mess of sizes now, according to their literature, 200 to 300 to 400 to 600, 700 and 800 in row crop and standard versions. Then they make the 900 or 950 in the tractor competitive with the model 820.

Of course, we get in the 300 to 400, the tractor with the Case-o-matic torque converter transmission—the three and four are the same except for that difference; the five and six are the same except the six has the Case-omatic transmission; seven and eight are the same except it has a Case-omatic transmission. Now from all re ports we get on the design of their engine, the cubic inch displacement, the bore and stroke and everything we can get from our suppliers as to what they are buying for their engines, they are using the same engine. As a matter of fact, the only difference Case has made is in its transmission. They’ve got a 12 speed transmission available in 200, 300, 400 and they’ve got a 12 speed transmission available, which means the standard gear box plus the auxiliary gear box between the gear box and engine there is an overdrive, an underdrive and a direct drive arrangement. Now they can take this outfit out and take the overdrive out of it and put in a reversing mechanism which gives them a transmission with eight forward or eight reverse speeds as near as we can figure out. It doesn’t sound possible but that’s what the Case people claim. They can take their overdrive out and have what they call a shuttle transmission, an eight forward and eight reverse speed, which is a transmission similar to the Dubuque direction reverser. That is what they call a shuttle system, moving a lever one way or another to go forward or backward with this speed range.