It is the middle of February, 15 degrees outside with a wind chill approaching zero. You should be sitting with the family next to a roaring fire. But no, you’ve got some work to do. Maybe you need to grind feed or scrape the driveway clear or, if you’re like many collectors today, you just want an excuse to play with your two-cylinder diesel.

But starting a diesel engine in the dead of winter is no easy task. You can plug in block heaters hours ahead of time, cross your fingers, and hit the starter, hoping your batteries can last long enough to start the tractor. Or you can stick with “obsolete” technology and use the often cursed and seldom respected pony motor.

Turn on the gas, flick the ignition switch. Hit the starter and choke; with a roar, the rumble of the tiny V-4 can be heard. Within minutes, you can put your hand on the side of the engine block and feel the warmth. After decompressing the diesel, you get ‘er rolling over, the pony at full song. Give the diesel compression and fuel and she fires right up. Not bad for something designed and built before man went into space!

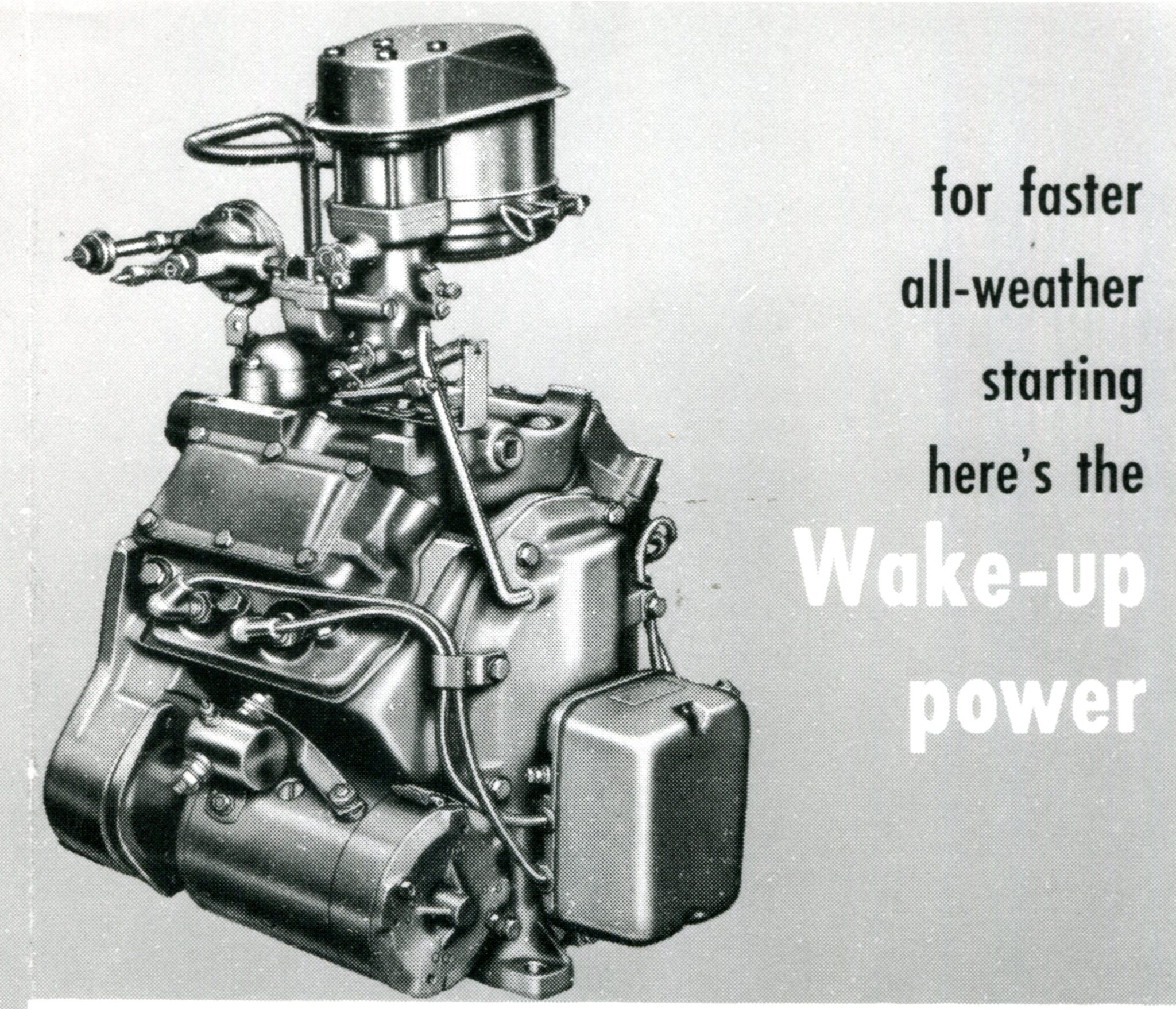

Known as cranking engines, pony motors, donkey engines, pups, or, more often, “that piece of junk,” probably no other Deere tractor accessory creates as much debate in the collecting community. These small gasoline engines were used to crank over the large two-cylinder diesel engines and also preheat the coolant and intake air of the diesel as well. For John Deere tractors, they started with the opposed two-cylinder engine in the model “R” in 1949 and then changed to a compact V-4 design (the focus of this article) in 1954 through 1960, used on the model 70-720-730 diesel and 80-820-830-840 diesels. Eventually, better technology allowed John Deere to offer “direct electric” starting, with a large starter and 24-volt system as an option on the 720-730 and 830-840 tractors.

Purists (or those just hard-headed and stubborn—like me) wouldn’t think of replacing a pony motor with a direct electric starter. Most normal people wonder why anyone would want to deal with the so-called hassle of a tractor with two engines. Ponies were fine for actual heavy farm use. You started the tractor in the morning and didn’t shut down ‘til dusk. For off and on operations—like a chore tractor or today’s parade usage, they seem to be a nuisance. Unfortunately, the V-4 ponies have also gotten a reputation for unreliability that they don’t deserve.

You may have noticed that almost every pony you see running emits enough smoke to kill all mosquitoes in the tri-county area. No, it is not a two-stroke engine. NO, it was not made to smoke. Some barely have enough power to turn the diesel over while decompressed, much less under compression. These engines can run on three or two cylinders and they don’t sound very different, but just seem very weak! If the pony is in good shape, it will run with little to no smoke and can crank over the diesel under compression with no problem! Many people have used the small engine to move the tractor for short distances.

The number one killer is neglect—a lack of maintenance. The engines only hold a quart or so of oil, with no real filter, just something resembling a window screen. It doesn’t take long for any contamination to create major problems when running up to 5,000 to 6000 RPM. Check the oil level every time (a pony veteran will also smell it for gas fumes) and change it often. A leaky fuel shutoff will fill the crankcase full of gas. A leaky water pump will fill it full of antifreeze/oil sludge. Neither is good for bearings.

When changing oil, you are supposed to let it dump into the diesel crankcase. If you don’t want to change your diesel oil at the same time, you could suck out the pony oil instead, using a small electric drill driven pump.

If your oil gets thin and gas smelling, you have to remember to use the fuel shutoff every time you kill the engine and it must work without leaking by. The automatic shutoffs can be rebuilt. So can the manual valve. Just take it apart and gently polish any grooves out of the needle, and it should shut off fine. I chuck them in a drill press to spin while I polish.

Take a look at the fuel tank. Is it rusty inside? This will plug up the carburetor quickly. If so, try cleaning out the rust with phosphoric acid. And if your tractor is an early one without a sediment bowl, adding one may be a good idea. I used one that is for a John Deere 110 garden tractor from www.hapcoparts.com. It’s not correct but fits just fine and is much cheaper than an original style. I had to remove the shutoff valve to screw the bowl into place, then reinstalled.

The heart of the cooling system is a simple gear-driven pump. However, the seals do go bad in this pump (especially if the tractor has sat for years) and the pump shaft can be pitted. There is a weep hole in the bottom of the pump that should let out any fluids (oil or antifreeze), but it is often plugged up or just can’t keep up with the leaking seals! This will let antifreeze flow directly into the crankcase when the engine runs. I learned the hard way that this has to be fixed immediately! The pump is a PAIN to remove without pulling the whole engine (almost 250 pounds), but it can be done. You may have to loosen the pony on an 80 series and slide it over to get the pump out. Then you can use a small press to remove the impeller and then replace the seals. Make sure you don’t disturb the backlash settings or lose the shims for the drive gear!

You will note the various coolant tubes going in and out of the engine, all sealed by O-rings. To avoid seeps and leaks on a nice shiny paint job, make sure the ends of the tubes are smooth and rust-pit-free. If not, use JB Weld or a metal filler to fill smooth. Also, you will want to check out the thermostat used in later engines. Make sure it actually opens at 100 to 115 degrees! I’ve yet to find a new replacement for that low temperature. Some marine outboard engine thermostats have low temp settings…try looking there if you really need one.

If you still have an internal coolant leak and you just can’t find it, the pony motors have wet sleeves and the O-rings are probably leaking. To remove these sleeves, you’ll need a very good puller or you might need to be violent and use a hammer and brass punch. The block is often full of rust and crud, making these sleeves VERY hard to remove. When cleaned out, they should go back in easily.

A common complaint is the ignition system. First, the V-4s use a distributor, NOT a magneto. The distributor is very simple; there isn’t even a vacuum advance. All you will find is a set of two coils, condensers and points…one for each pair of cylinders. Each cylinder will fire on the compression stroke AND exhaust stroke.

The ignition coils are very sensitive to voltage. There is a resistor on the ignition switch which reduces the voltage from six volts to about 4.5 and a bypass on the starter for a full six volts when starting. Some experimentation by others has found that the new coils made today can handle the full six volts all the time and they actually work better, too! I haven’t tried this yet, but keep that in mind if you have weak spark problems.

Do NOT ever jump a pony motor with 12 volts. And NEVER leave the ignition switch on for long if the pony isn’t running. Doing either of these things will burn out the coils and burn a big hole in your wallet to replace them.

There is a popular fix to the coil burning problem. Use an oil pressure switch to control power to the distributor. It has been detailed in a past GM article. However, this still won’t stop things from burning if you jump it with 12 volts!

The spark plugs on these engines can be a pain to change. Some probably haven’t been changed since Eisenhower was in office. There isn’t much room on a row crop, especially the two toward the dash. At least, it looks that way. Try removing the starter…now there is plenty of room to work with an open-ended wrench. I’ve used Champion J8Cs with no problems. Of course, everyone else has their favorite brand of plug!

You don’t want to forget the air cleaner—it does double duty, as air cleaner for the pony AND the diesel crankcase breather. Fumes from the diesel crankcase go from a small hole (where you normally drain the pony oil) into the pony timing cover and crankcase, then through a tube, into the air cleaner, and then finally out. A long journey! Unfortunately, this little oil bath air cleaner is very rarely checked, as it is often out of sight and out of mind especially on an 80 or early 820—well under the hood. It is worth some effort to clean out the air cleaner body and to keep the bowl full of oil. It will keep both of your engines in good shape. Another thing to be concerned about—if your diesel engine is worn enough to have significant blow-by, it can actually blow the oil out of this air cleaner!

It is also a good idea to make sure the various carburetor/governor linkages are set correctly. A properly functioning governor is needed to get good power and RPM. Some are missing the governor spring…meaning it won’t come off idle. When I first bought my 80, the pony was rigged to run at full RPM all the time. A minor adjustment had it working correctly. My 70 diesel pony wouldn’t run right after I rebuilt it. I messed with the adjustments for a couple days with no progress until I realized that it had the wrong spring. Remember also that the top speed (no load) did change, from 6000 in the 70 and 80 down to 5000 on the later tractors. Most of us just stick to the lower 5000 RPM.

The cranking engagement adjustments and clutch adjustments are best described in the service manuals. The single lever decompression/engagement system on the 70Ds is often messed up. The two lever system on all the others isn’t as bad. Get out the books and you can get it working right. If you have problems with grinding instead of engaging, first make sure your flywheel gear is in good shape and the matching pinion on the pony. Grinding is also caused by a greasy pinion brake pad—try to clean it with brake cleaner. If there is too much wear on the brake, you’ll have to replace it, which means pulling off the pony or the transmission at least.

The transmission and clutch of these engines is as simple as it gets—not much to go wrong. However, there is an overrunning clutch, which is supposed to avoid pony engine damage if you leave the pony engaged to a running diesel (though I don’t suggest doing it!). The little rollers or drive can become worn and not work—or cause problems, not allowing the pony to engage properly. One other note—while the engine itself is easily swappable between all tractors, the transmissions are very different from a 70 series and 80 series.

When the pony is running, its exhaust is routed around the diesel air intake, acting as a preheater for the diesel intake air. You definitely want to make sure that there are no internal leaks in this heat exchanger. You don’t need your diesel engine sucking in pony exhaust. Even worse, this would allow the diesel to suck in unfiltered air. This can be checked by holding your hand at the pony exhaust (not running!) while the diesel is running. If you feel suction, there is a leak. Also make sure the diesel intake drain hole is open, which allows moisture out of the cast iron portion (on the 70 series tractors). It is above the diesel exhaust manifold on the left side.

Besides maintenance, the other pony killer is plain abuse. These engines are only used for few minutes and many people (used to a “turn-key” start) don’t want to wait even that long to get moving. They need to warm up at idle. Running at full RPM under a load with no warm-up is bad for any engine. Would you do it to your new car or truck? And your modern vehicle doesn’t often hit 5000 RPM.

After warm-up, get the diesel cranking decompressed until there is oil pressure, give it compression, THEN fuel. When the diesel fires, you must remember to always shut the gas off first and let the engine die before shutting off the ignition. If you don’t, the pony will slowly get filled with gas, as it sloshes out of the fuel bowl while driving.

Don’t forget that most of these engines haven’t seen a rebuild in 20 years, if ever, and the abuse of cold running and diluted or old oil adds up. However, if the pony can crank over the diesel under compression with no problem and has good oil pressure, it is usually a good idea to let sleeping dogs lie and live with the smoke. If you tear one apart, the common cause of smoke is worn valve guides and plugged oil return holes in the heads. A set of rings wouldn’t hurt either!

If your pony is really bad internally, parts are out there. Parts can be expensive for an engine of its size but you have to remember, these engines haven’t been produced new by John Deere for 40-plus years. And once you do fix it, it should outlast you!

Just make sure you know what parts you need. There are early engines (70/80, green dash 720/820) and late engines (black dash 720/820 onwards) with lots of changes. Many parts interchange between the engines but some don’t! You may find a later engine on an early tractor or a mixture of parts, as on my 70. This leads to confusion! Parts books are your friend!

Many parts can be found at Deere: rings, valve guides and valves, O-rings and seals. Larger parts such as new pistons and connecting rods are available, albeit very expensive. For some reason, pony gasket sets are now a bit pricey. Try ordering individually what you need and making the rest yourself.

The availability of parts from sources other than Deere is definitely getting better for these engines. There are plenty of suppliers of used parts in Green Magazine. I’ve seen aftermarket undersized connecting rods on eBay, plus various NOS and used parts listed there on occasion as well.

For those who still wish to dump the pony motor in favor of direct electric start, give it some thought. I had to rebuild the pony in my 70D in early 2006. It broke a connecting rod and caused a bit more damage due to antifreeze in oil. Including a spray welded crank, new main bearings, four new connecting rods, rings, head work, seals, gaskets, etc., I spent less than $1,500 to get it in great shape…it doesn’t smoke either.

You could easily put that much money into a correct John Deere style 24 volt electric start conversion by the time you add up rewiring, certain gauges, starter bracket, starter, generator, crankcase breather, intake manifold, battery box, and batteries. Not to mention a hood without the door! Even a short cut 12 volt conversion can involve large sums of money. And if you live in a cold climate, you will regret it, unless you park it for the winter. A pony motor in better shape would cost a lot less to fix than mine, still be correct and completely functional too.

If you do get a tractor with a pony, you will be keeping a bit of 1950s nostalgia alive—just like big chrome bumpers and tailfins. Something to keep the kids and grandkids guessing, “Why does that tractor have two engines?”

Author’s note: I’ve only owned two pony start tractors, a 70D and 80, for relatively few years. This article would not be possible without help and advice from friends on various message boards who have owned these tractors for much longer than me. I could list them all, but it would take a page or two and I would miss someone. It is appreciated, even if you didn’t realize you were helping!

More thanks have to go to my father and grandfather for dealing with me and this hobby. They have only themselves to blame…they started it!

V-4 cranking engine specs and changes (not a complete list, but it includes the major changes)

Speeds (model 70 + 80)

Slow idle: approximately 3000 RPM

Fast idle: 6000 RPM

Load: 5500 RPM

Speeds (720, 730, 820, 830, 840)

Slow idle: approximately 3000 RPM

Fast idle: 5000 RPM

Load: 4500 RPM

Bore: 2 inches • Stroke: 1-½ inches

Cubic inches: 18.85

Oil pressure: 25 PSI

Distributor point gap: .020”

Spark plug gap: .025”

Tappet lever (rocker arms) clearance: .008”

Cranking engines received these changes in the 70 and 80 models:

- Separate starter pedal added to 70 models at 7026870 to simplify linkage problems (field update kits available)

- Spring loaded transmission shifter at for 70 models at 7031300 for better pinion engagement

- Transmission oil capacity increased in 70 models at 7031300

- Clutch throwout bearing made greaseable at 7031300 and 8001700

Cranking engines used in green dash 720/820 had the following changes:

- All models now push button start

- All models now use the two lever engagement and decompression

- Connecting rods changed from F1806R to heavier F3300R

- Engine speeds slowed by 1000 RPM with governor and linkage changes

- Muffler added

- Tappet levers made slightly thinner for better hold of adjusting screws at 7212907 8202599.

Cranking engines got the following changes with the black dash 720/820:

- Separate serial number added to each engine

- Main bearings changed from 1-1/8” diameter to 1-1/2″ (changing the block and main bearing cap)

- New timing gear cover and shortened dipstick for increased engine oil capacity to 1-1/2 quarts

- New oil pump and pickup screen, placed on bottom of crankcase

- New oil pressure relief setup with pin to hold spring in place

- New cylinder heads

- New camshaft

- Pushrods made heavier with cup ends to hold position better

- Cam gear changed with plate to avoid wear from governor balls

- Oil pressure fuel shutoff

- Air cleaner made larger and more accessible (820 only)

- Thermostat and water bypass added to manifold/waterpump

- Larger bearing used on clutch shaft (820 only).

Cranking engines used on earlier tractors with small main bearings sometimes received an update kit with new crankshaft, using a 1-1/8 inch main bearing on one end (to fit in the original block) and 1-1/2 inch main bearing on the other end (to fit in a new main bearing housing). These crankshafts appear to be hand stamped with part number F3522R.